5 Questions About: Vietnam

Cracked Back Book Reviews: June 2008

10 Things John Wayne Would Never Do

5 Questions About: Generation Y

The 10 Greatest Drunks in Cinema History

Signs That the U.S. is Rome

How Hollywood Ruined an Epic Poem

5 Questions About: Linda Strawberry

Is Indiana Jones a Misogynist?

Literary Criticism

Fantastically Bad Cinema

Essays

Under God's Right Arm

June 2006

July 2006

August 2006

September 2006

October 2006

November 2006

December 2006

January 2007

February 2007

March 2007

April 2007

May 2007

June 2007

July 2007

August 2007

September 2007

October 2007

November 2007

December 2007

January 2008

February 2008

March 2008

April 2008

May 2008

June 2008

July 2008

August 2008

September 2008

October 2008

November 2008

December 2008

January 2009

February 2009

March 2009

Alcoholic Poet

Baby Got Books

Beaman's World

BiblioAddict

Biblio Brat

Bill Crider's Pop Cultural Magazine

The Bleeding Tree

Blog Cabins: Movie Reviews

A Book Blogger's Diary

BookClover

Bookgasm

Bookgirl's Nightstand

Books I Done Read

Book Stack

The Book Trib

Cold Hard Football Facts

Creator of Circumstance

D-Movie Critic

The Dark Phantom Review

The Dark Sublime

Darque Reviews

Dave's Movie Reviews

Dane of War

David H. Schleicher

Devourer of Books

A Dribble of Ink

The Drunken Severed Head

Editorial Ass

Emerging Emma

Enter the Octopus

Fatally Yours

Flickhead

The Genre Files

The Gravel Pit

Gravetapping

Hello! Yoshi

HighTalk

Highway 62

The Horrors Of It All

In No Particular Order

It's A Blog Eat Blog World

Killer Kittens From Beyond the Grave

The Lair of the Evil DM

Loose Leafs From a Commonplace

Lost in the Frame

Little Black Duck

Madam Miaow Says

McSweeney's

Metaxucafe

Mike Snider on Poetry

The Millions

Moon in the Gutter

New Movie Cynics Reviews

Naked Without Books

A Newbie's Guide to Publishing

New & Improved Ed Gorman

9 to 5 Poet

No Smoking in the Skull Cave

Orpheus Sings the Guitar Electric

Polly Frost's Blog

Pop Sensation

Raincoaster

R.A. Salvatore

Reading is My Superpower

Richard Gibson

SciFi Chick

She Is Too Fond Of Books

The Short Review

Small Crimes

So Many Books

The Soulless Machine Review

Sunset Gun

That Shakesperherian Rag

Thorne's World

The Toasted Scrimitar

This Distracted Globe

Tomb It May Concern

2 Blowhards

Under God's Right Arm

A Variety of Words

The Vault of Horrr

Ward 6

When the Dead Walk the Earth

The World in the Satin Bag

Zoe's Fantasy

Zombo's Closet of Horror

Bookaholic Blogring

Power By Ringsurf

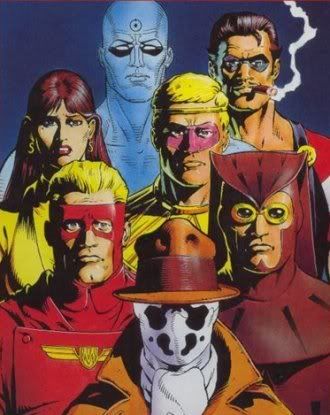

Revisiting the Breakthrough Graphic Novel 22 Years Later

Writer Alan Moore created “Watchmen” in 1986 because he wanted to push the comic book beyond adolescence into what he called “a superhero Moby Dick.” The 12 edition comic book series – and later the compilation graphic novel – went on to win the Hugo Award and to be named one of TIME magazine’s 100 Best Novels since 1923.

Writer Alan Moore created “Watchmen” in 1986 because he wanted to push the comic book beyond adolescence into what he called “a superhero Moby Dick.” The 12 edition comic book series – and later the compilation graphic novel – went on to win the Hugo Award and to be named one of TIME magazine’s 100 Best Novels since 1923.

There is little doubt that “Watchmen” blazed a new path for comics – especially superhero comics. But did it really have the impact of Art Spiegelman’s “Maus,” which was first published in 1973 or even Gil Kane and Archie Goodwin’s “Blackmark” (1971), arguably the first “graphic novel” published in the

And did

First let’s explore the narrative. “Watchmen” is a dark story. It captures the pre-apocalyptic fears of modern American and Western Europe in the mid-to-late 1980s as the Cold War rhetoric between the Soviet Union and

The story centers on a group of masked adventurers in an alternative universe to our own 1980s (one in which Nixon remains president). The “superheroes” are, in fact, regular human beings with no real powers – other than extraordinary physical conditioning and mental acumen. Doctor Manhattan is only character with superhuman skills as a result of a scientific experiment gone wrong.

The novel opens with the murder of the Comedian (Edward Blake), one of the costumed avengers affiliated with the CIA and other secret government agencies. Rorschach, a second costumed hero, who refused to give up his vigilante lifestyle even after the

Through the investigation, the novel enters the lives of the various costumed heroes: Nite Owl (a first and a second version), Ozymandias, Captain Metropolis, Silk Spectre (first a mother, then her daughter), Doctor Manhattan, the Comedian, and Rorschach. The characters are all flawed – some of them grossly so. The Comedian, for example, is a misogynist and rapist and Rorschach is a sociopath.

and Rorschach is a sociopath.

Rorschach thinks he has uncovered a plot to murder all of the costumed adventurers and enlists the help of his former partner, Nite Owl, to help him. Meanwhile, the super powerful Doctor Manhattan, who has the ability to restructure reality and to manipulate time and space, continues to struggle with relating to regular human beings. After rumors that being near him causes cancer, he banishes himself to Mars.

The murders end up being the work of the genius Ozymandias, who has concocted an elaborate scheme to bring the world’s nations together: a fake alien invasion that kills thousands of people. His costumed friend figure out his plot, but are unable to stop it. And, in the end, it turns out Ozymandias is right.

The weakest part of “Watchmen” is the plot, especially the comic book ending. There are so many holes in the logic and execution of Ozymandias’ scheme that it’s difficult to follow or understand. But the plot isn’t really the driver in “Watchmen” – it’s the characters and

The novel is heavy on symbolism (lots of watches and clocks, for example) and mood – but differs from comic books from the time period by providing a straight forward and objective point of view. It’s up to the readers – not Moore as the author – to figure out how to react to the action on the page.

Another interesting device is

The artwork in “Watchmen” feels like a throwback to the Golden Age of comics in the 1950s and 1960s (in fact, primary artist Dave Gibbons credits Norman Rockwell as an inspiration for “Watchmen”). There’s a cinematic feel to the artwork – especially of noir films with the shadows and darkness. But there’s surprising little movement to the graphics and sometimes the panels feel a bit inert.

So how influential was “Watchmen”? It is generally credited with taking superhero comics from low-brow kid’s entertainment and catapulting into high-brow art. That’s no minor achievement. “Watchmen” also ushered in an era of dark and bleak story lines around comic book superheroes (can we blame “Watchmen” for the death of Superman and Captain

But

Influential?

Yes.

But a hallmark of great literature?

No.

Maus Revisited

The 5 Most Addictive Arcade Games

Labels: Alan Moore, book review, comics, superheroes, Watchmen

StumbleUpon |

StumbleUpon |

del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |

Technorati |

Technorati |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 License.

The Template is generated via PsycHo and is Licensed.